一位意大利汉学家与王羲之的不解之缘

2020-05-08

2020-05-08

我再度启程赴中国前,母亲问我这次去做什么,我告诉她:意大利有达·芬奇,比他再早1000多年,中国也有一位“达·芬奇”,叫王羲之,他的书法让人叹为观止,值得全世界给予关注并投入研究。我这次就是去交流自己的研究成果。

自1998年第一次从意大利到中国起,我已经记不清来过多少次了。除了北京、上海这样的大城市,我钟爱的还有天津、西安、洛阳这些具有历史底蕴和文化内涵的城市。当然,还有我的书法研究启蒙地——杭州。

研究中国的“达·芬奇”

2019年春天,当我再度启程赴中国前,母亲问我这次去做什么,我告诉她:意大利有达·芬奇,比他再早1000多年,中国也有一位“达·芬奇”,叫王羲之,他的书法让人叹为观止,值得全世界给予关注并投入研究。我这次就是去交流自己的研究成果。

那次学术会议——绍兴论坛“源流·时代——以王羲之为中心的历代法书与当前书法创作”,云集了各国学者。这是我第一次在兰亭参加曲水流觞,受邀当选“二王学研究中心”的特聘专家。

2019年年底我再一次来到绍兴,是绍兴图书馆邀请我作公众演讲。

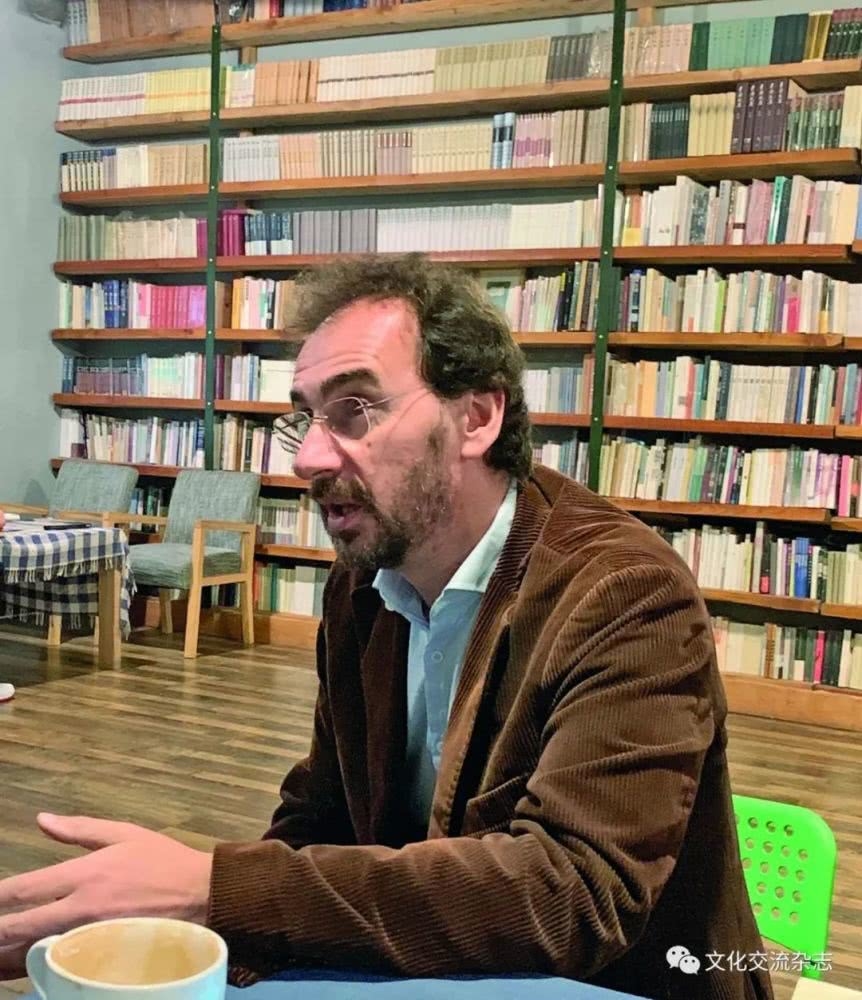

●2019年底,毕罗(Pietro De Laurentis)在绍兴图书馆举办讲座后,在荒原书店接受记者采访。 (王宏超 摄)

很多人对我的研究感到好奇,主要是因为没有很多西方人专门做书法研究。

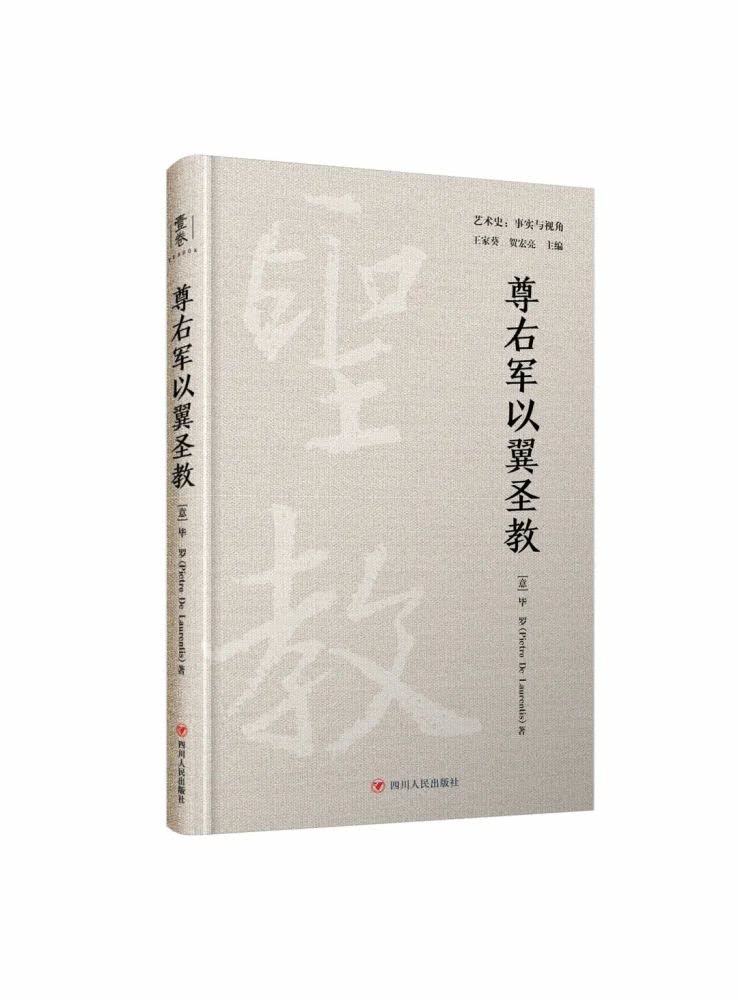

绍兴论坛结束以后,四川人民出版社邀请我撰写一部跟王羲之书法有关的著作,名为《尊右军以翼圣教》,预计于今年面世。

起初在杭州留学时,我并没有想到今后自己将出版意大利文、英文、中文版本的与中国诗词、书法研究相关的著作。对我来说,这些只是我汉学研究向纵深推进过程中的阶段性成果。汉学文化博大精深,值得探究的内容实在太多了。

我从小就有一种观念:文化不等于书上所记载的知识。上学时,我不喜欢光看书不出门的同学——所谓的“书呆子”(意大利语叫secchioni)。虽然自己成绩还比较好,我也尽量避开为读书而读书的人。因此,我上大学攻读中文专业的时候,发现一大片“文化绿洲”向我敞开怀抱。当然,书上介绍的中国文化确实很有魅力,但对我来说,兴趣最大的不是抽象的博大精深,而是土生土长的中国人本身。汉字和书法是我和中国人打交道的媒介。

在杭州“靠近”书法

我第一次留学中国是1998年,在北京。有同学看不惯我用毛笔写字,他们大概认为,我的水平不够,这好像在“冒犯”一种悠久的文化传统。但是我想得正好和他们相反:“这是一项你喜欢的东西,干吗不去靠近它?”我回顾这20年和中国文化包括书法的结缘,基本上可以用“靠近情缘”这个词来概括。而我真正“靠近”它,应该说不是在北京留学那次,而是将近三年的两次在杭州的留学。

第一次是2000年—2001年,我留学中国美术学院(以下简称中国美院);而后是2004年—2005年我留学浙江大学。我对中国的基本看法,包括我对书法的认识和研究,基本上都成型于这两个时间段。

1999年年底,我还在意大利读大学时,就已经和我的书法老师相识了。他的名字叫王承雄,上海人,直到现在,他还在指导我学习毛笔字。我和他一见如故,性格上很合得来,向他学习书法后也取得一些进步。但我和他都很清楚,想要了解书法是怎么回事,除了看书和请教老师以外,还必须进入原生态的书法文化环境。当时在意大利,除了王老师,我还有几个中国朋友,都是上海人,他们也是艺术爱好者。当我与他们聊起自己打算去中国全面学习书法时,他们都建议我去杭州,一方面因为杭州有着浓厚的书法文化底蕴,另一方面杭州有中国美院。

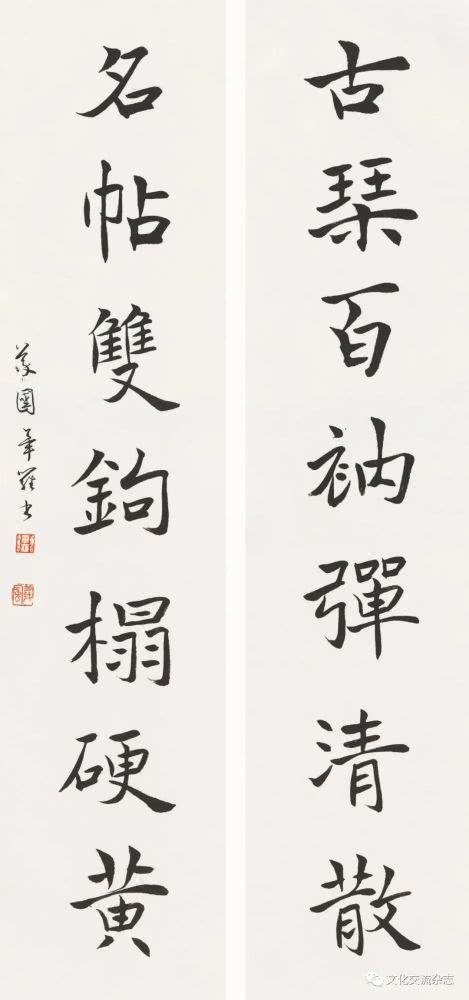

●毕罗书法:楷书古琴名帖联。

当时的中国交通和现在相比,简直是天壤之别。虽然大城市的地铁系统已经相当完备,但是铁路并没有像现在的高铁这么方便。我记得那时候上海南站还没修好,只能从梅陇站坐车到杭州城站。

作为中国美院留学生,我们居住在中山中路。2000年下半年的杭州和今天的杭州不太一样,那时的中山中路还不是现在这般繁华的旅游街区,基本上都是普通老百姓的居住地。当时杭州的交通也不像现在这么拥挤,汽车也不是非常多,自行车当然不少。我自己也买了一辆,但是我更喜欢走路,确切地说,叫“乱走”。基本上是开始走一条路,然后走向引起我注意的角落、建筑物或门面。就这样要么继续走,要么拐弯钻进小路,要么停下买点小吃,基本上不会走回头路。别说导航,我连手机都没有,查地图也觉得有点烦,不如就这样散步。当然,这样随心所欲地走,迷路的可能性不小,但是我觉得无所谓,我在中国一直觉得到处都很安全。万一实在找不到路了,打个车就可以回宿舍。

我们书法留学生班,一半是欧洲人,一半是日本人。虽然我们欧洲人坐在教室的左侧,日本人坐在教室右侧,但是我们之间的交往并没有隔开,反而相处得非常好。当然,欧洲人和日本人在学习书法方面不可能在同一个水平上,因为我们很难把握汉字形体。作为中文系的学生,我倒还好,但其他欧洲同学都是学其他专业的,对他们来说,写字就是“描”——看着字帖写,如果自己发挥一下灵感挥毫,就成了画抽象画。

这种不太扎实的中国文化修养带来的问题是,在美院进修书法基本上等于是学写字。可是,我申请中国政府奖学金留学杭州的目标是要写我的毕业论文——即后来2002年年底在意大利答辩的《正书之源流》。所以除了写字以外,我还对学术性的书法研究有兴趣,但是美院在这方面的指导不是很多。这部分文史知识是我在意大利考上博士研究生以后第二次留学杭州时才补上的。

从做研究到做交流

2003年年底考上博士以后,我立刻决定离开意大利去中国留学,因为我读博士不是为了获得文凭,而是为了好好做书法研究。起初报的课题是中国早期的书法文献,但意大利包括所有的西方大学,别说书法文献,连做书法史研究的基本条件都不具备,这意味着如果要好好做这方面的研究必须到中国去求学。另外,我和别的研究书法的汉学家有很大的不同,我非常在乎书法的实践,并认为写书法是研究书法的基础和出发点,而且也只有到中国学毛笔字才有希望获得真正的进步。我以前这么认为,到现在还是这样认为。

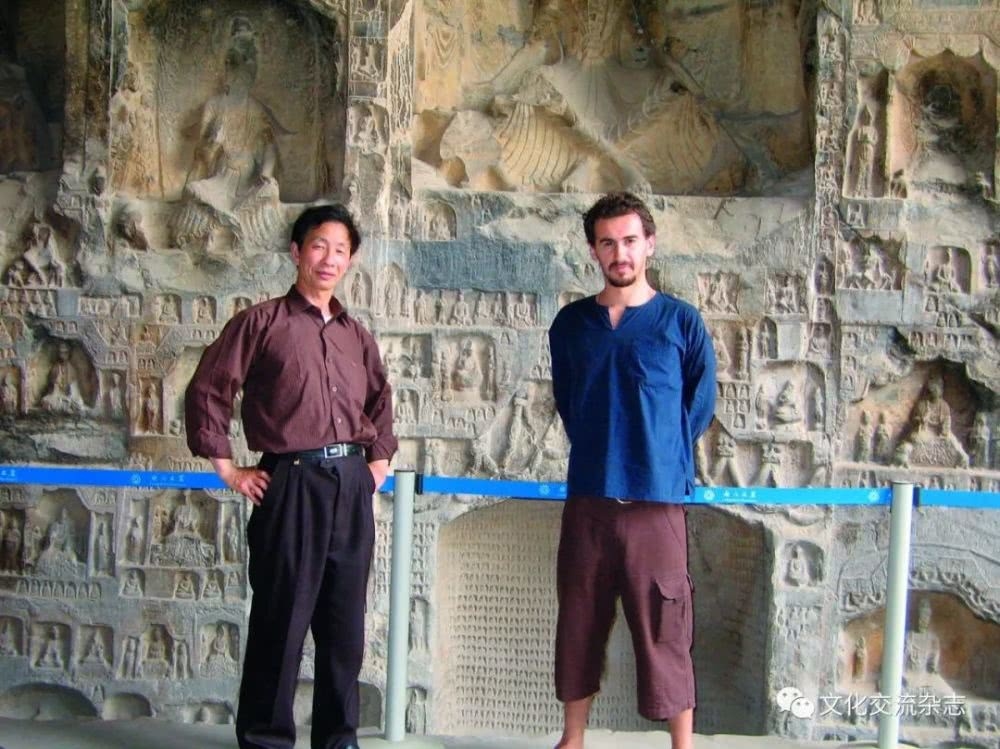

●2006年河南洛阳,毕罗与洛阳龙门石窟研究院专家张乃翥。

有意思的是,我博士论文的选题后来改成孙过庭的《书谱》了。2001年春天我还在中国美院留学时,有一天在解放路公交车站的玻璃窗里看到正在展示的《书谱》长卷照片。我之前只知道《书谱》一页一页的字帖,看到长卷(真迹是906厘米长),觉得很震撼,更没料到,后来孙过庭成了伴随我好几年的宗师和研究对象。

2004年年初,我又到了杭州,这次是到浙江大学(以下简称浙大)留学。我第一次留学杭州,在浙江大学认识了一位中国老师,名字叫易容。我于1999年在意大利接待过复旦大学教授吴中杰先生,她是吴老师的博士生。2003年,她帮我联系了陈振濂教授,并且推荐我做他的硕士生。我当时报的其实是中文系汉语言文字专业,所以在学校学习,一半的时间在艺术系还有一半在中文系。

在浙大读书时,我真正进入了学术研究的关键时期,从幼稚被动到逐渐拥有历史透视和文化视角,这除了跟浙大优越的学习条件相关之外,还跟我当时交往的朋友有关,尤其是与我同坐一间教室的姚宇亮——如今他是广州美术学院的教授。姚兄和其他朋友让我注意到书法作品和书法文化中好多细微的地方,如果没有他们的示范或提醒,光靠我自己的悟性是很难注意到的。

另外,因为学习陈老师的硕士课程的需要,学校要求我写论文。我那时候写过一篇意大利文的硕士毕业论文,于是又写了一篇短短的《〈笔阵图〉点画形态考》。

我用一年多时间钻研《书谱》并写成文章《〈书谱〉文体考》,后来它成了我的博士论文、英文专著的核心内容。我记得很清楚,2005年春天陈老师看了这篇小文之后,在课堂上公开称赞说如果再润色一下就可以发表,我当时觉得非常得意,也算是人生的一次发现自我吧。

浙大的硕士没读完,我权衡再三,离开杭州回到母校继续撰写博士论文。这其实也是我发展的需要。作为西方青年汉学家,要有治学的学术规范,要有国际学术的视角,才能和别的学者进行对话和交流,永久留在中国也未必是最好的选择。回到意大利后我完成了博士毕业论文,在意大利东方大学任教,并保持与中国学者的交流与联系。

后来,我还先后到过杭州很多次,一方面是见朋友,一方面是参加学术活动。无论时间过得多快,周围变化多大,心里存放着的美好回忆想删也删不掉。

2018年,我把自己近二十年的中国书法学习上的经历撰写成十几篇文章,陆续刊登在《书法》杂志上,算是对自己多年来游历中国的记录。中国人说“读万卷书,行万里路”,我也愿意把行走的经历分享给更多朋友。

2007年至2019年下半年,我在中国财经大学、广州中山大学、陕西师范大学、上海图书馆、绍兴图书馆等多所大学或图书馆,作了面向专业学生及公众的演讲。2017年及2019年,我先后两次在复旦大学中华文明国际研究中心及中华古籍保护研究院做访问学者。2019年11月,我在复旦大学进行为期三个月的访学。将近十五年的时间里,我在中国举办各种讲座,每场讲座都与听众有特别开心、活跃的互动,这是我最珍惜的一种体验。这也确实证明,书法不仅仅是高校的艺术,也是属于全民的一种文化精髓。

Chinese Calligraphy as I See It

I first visited China in 1998. Since then I have visited the oriental country numerous times. Of the cities in China, I love Beijing and Shanghai for various reasons and I love Tianjin, Xi’an and Luoyang for their rich historical heritage and cultural wealth. Hangzhou is unique, however, because it gave me enlightenment on Chinese calligraphy.

In the spring of 2019, I visited Shaoxing and attended a ceremony in honor of Wang Xizhi (303-361), a great Chinese master of calligraphy, whom I referred to as China’s Da Vinci when I explained the purpose of my visit to my mother. “His amazing calligraphy demands the attention of the world. I will submit my research result and engage in exchanges with international colleagues,” I explained.

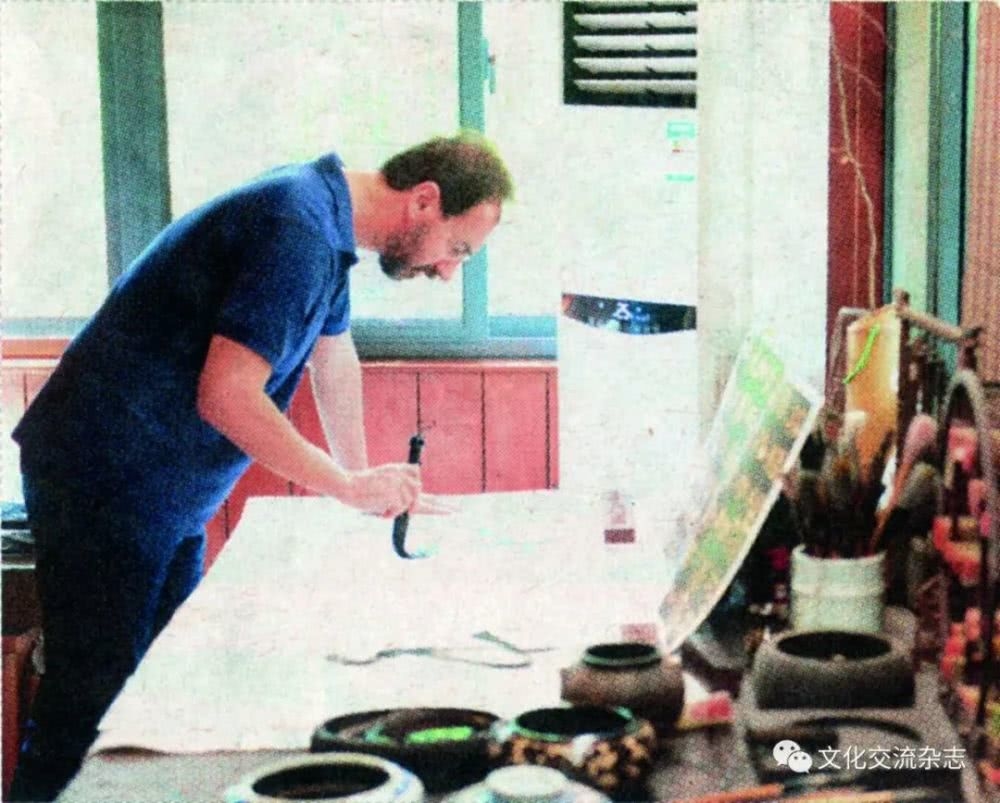

●毕罗先生现场创作。

International and Chinese scholars attended the event. I was engaged as a specialist at a research center there. At the end of 2019 I gave a lecture at Shaoxing Municipal Library. Many people there were curious about my research, mainly because they knew there were few westerners specialized in Chinese calligraphy. After the public lecture in Shaoxing, Sichuan People’s Press engaged me to write a book about Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy. The book is scheduled to be published in 2020.

When I began studying Chinese calligraphy in Hangzhou in 2000, I had the slightest idea that I was to write books in Italian, English and Chinese about Chinese poetry and calligraphy. The first calligraphy course I took at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou lasted from 2000 to 2001. The second calligraphy course I took at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou lasted from 2004 to 2005. My understanding of China and calligraphy took shape during these two special courses.

I took interest in Chinese calligraphy in 1999 in an Italian university. I had a Chinese calligraphy teacher named Wang Chengxiong, a native of Shanghai. I have been practicing Chinese calligraphy under Wang’s guidance since then. I met Wang and we became friends pretty fast. With him as my teacher I made fast progress in writing Chinese. I had a few Chinese friends who also hailed from Shanghai. When I chatted with them about my intention to study calligraphy in China, they unanimously suggested Hangzhou: Hangzhou is a city of calligraphy and the city hosts China Academy of Art. I knew clearly that I needed to be in an authentic atmosphere to experience Chinese calligraphy.

So I came to Hangzhou in 2000. As an international student of China Academy of Art, I lived in a special dorm near the campus. Back then, Hangzhou was relatively underdeveloped. I bought a bicycle and pedaled around randomly in my spare time. Whenever I started a bike adventure, I picked a road arbitrarily. As I pedaled along, I enjoyed going wherever distractions and attractions led me. I never followed the same road back. I just moved ahead. I felt safe in China and even if I got lost, I could easily find a taxi to get back to the dorm.

The course at the academy was a primary one. What I learned there was the essentials of how to use a brush pen to write. However, this course did not give me enough to write a dissertation on the sources of Chinese calligraphy. I had applied for a Chinese scholarship for writing the dissertation to be submitted and then defended toward the end of 2002 in Italy. I was interested in academic study of Chinese calligraphy, but the course I took at the academy was in another direction.

After I became a doctoral candidate toward the end of 2003, I immediately made up my mind to take a course in Hangzhou, for I really wanted to know everything about Chinese calligraphy. I needed to take a close look at the calligraphy literature in early history of China. Such a study was not likely in Italy. And unlike some sinologists who studied Chinese calligraphy, I wanted to be an excellent calligrapher. Writing like a qualified calligrapher would help a great deal for a profound academic study of calligraphy. Only in China can an international student become a really good calligrapher. I still think so today.

Interestingly enough, it was during my second study in Hangzhou that I dismissed the previous doctoral dissertation and decided to focus on Treatise on Calligraphy by Sun Guoting (646-691), a Chinese calligrapher of the early Tang Dynasty. The work was the first important theoretical work on Chinese calligraphy, and has remained important ever since, though only part of it survived. I happened to see a copy of the treatise in a display gallery by a bus stop in Hangzhou in the early 2001 when I was taking my first course in calligraphy at China Academy of Art. I was profoundly impressed by the grandeur and elegance of the long scroll replica which is 9.06 meters long.

●2019年12月14日,毕罗在上海图书馆举办讲座,与上海图书馆馆长陈超合影。

The second course I took was a graduate course at Zhejiang University. I studied under the guidance of Professor Chen Zhenlian, a prominent calligrapher. It was at Zhejiang University that I got really immersed in academic studies. I learned to view academic issues from historical and cultural perspectives. I made rapid progress largely because of the rich resources available at the university and because I got useful help and feedback from classmates in the same course. Among them was Yao Yuliang, now a professor of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Yao and other friends directed me to take a closer look at the nuances of calligraphy, which I wouldn’t have noticed if they hadn’t guided or demonstrated to me. As I planned to write a treatise for the graduate course, I spent more than a year writing a treatise titled the Style of Treatise on Calligraphy in Chinese. In the spring of 2005, Professor Chen examined my treatise and praised me in front of all my classmates. He said the treatise was good enough for publishing with some minor amendments. I was very happy. This treatise later became the core of my doctoral dissertation. After the doctoral dissertation, I wrote a book which was centered on the graduate treatise.

I did not finish my graduate course at Zhejiang University. After weighing pros and cons of several options, I decided to give up the graduate course and go back to Italy to finish my doctoral study. As a sinologist in the west, I need to abide by an international academic perspective before I can conduct a dialogue with other sinologists. I finished my doctoral dissertation and attained a PhD degree. Now I teach at University of Naples “L’Orientale”. I have kept constant contact with Chinese colleagues and friends.

Since then I have visited Hangzhou many times for taking part in academic programs and meeting friends.

In 2018, I wrote a dozen articles about my 20-year experiences in China. They were published in Calligraphy, a professional monthly founded in 1977 and based in Shanghai.

From 2007 to the second half of 2019, I held public lectures at universities and libraries across China. The interaction between the public and me at these lectures was pleasurable and eye-opening. I cherish such an experience because I think the positive response of the public means that calligraphy is more than an academic subject studied only at higher education institutions and that it is a cultural experience the public appreciate and enjoy.

图书信息

《尊右军以翼圣教》

[意] 毕罗(Pietro De Laurentis)著

定价:64.00元

四川人民出版社·壹卷丨2020年4月

内容简介

本书是介绍名碑《集王圣教序》(立于673年1月1日,现存西安碑林博物馆)的著作,也是意大利汉学家毕罗专门研究《集王圣教序》的最终总结。《集王圣教序》巧妙地融入了中国历史上三位影响力甚大的人物——玄奘、唐太宗李世民和书圣王羲之的事迹。唐太宗、唐高宗时期的中国已经非常繁荣,是当时世界上最强大的帝国之一,首都长安是充满着国际气息的大都市,同时汉人文士也具有开放包容的性格。书法作为汉人文化独有的艺术,理所当然也会受到当时的文化氛围的薰染。本书一方面以严谨的文献基础与合乎逻辑的推理,论述了《集王圣教序》的立碑动因和历史环境,另一方面对此碑的制作和书法特征做了逐字的探讨。

作者简介

毕罗(Pietro De Laurentis),意大利汉学家,独立学者。1977年生于意大利,2007年获得拿波里东方大学汉学博士学位。曾在拿波里东方大学担任研究员,执教古代汉语、现代汉语和中国文学史等课程。毕罗热爱书法研究和实践,从1998年首次来华留学以来,与中国学术界保持密切联系,并且频繁在全国进行实地考察和专题演讲。

本文转载自《文化交流》杂志